Why Heat Damage Is Usually Invisible

Heat damage is one of the most misunderstood failure modes in sharpening—not because it is rare, but because it is quiet.

When steel is damaged by heat, there is often no discoloration, no visible deformation, and no immediate loss of sharpness. The edge may leave the bench performing aggressively, only to fail prematurely weeks or months later.

This post explains why heat damage is usually invisible, how it occurs without obvious warning signs, and why professional sharpening must treat thermal control as a structural requirement rather than a precaution.

Heat Does Not Announce Itself

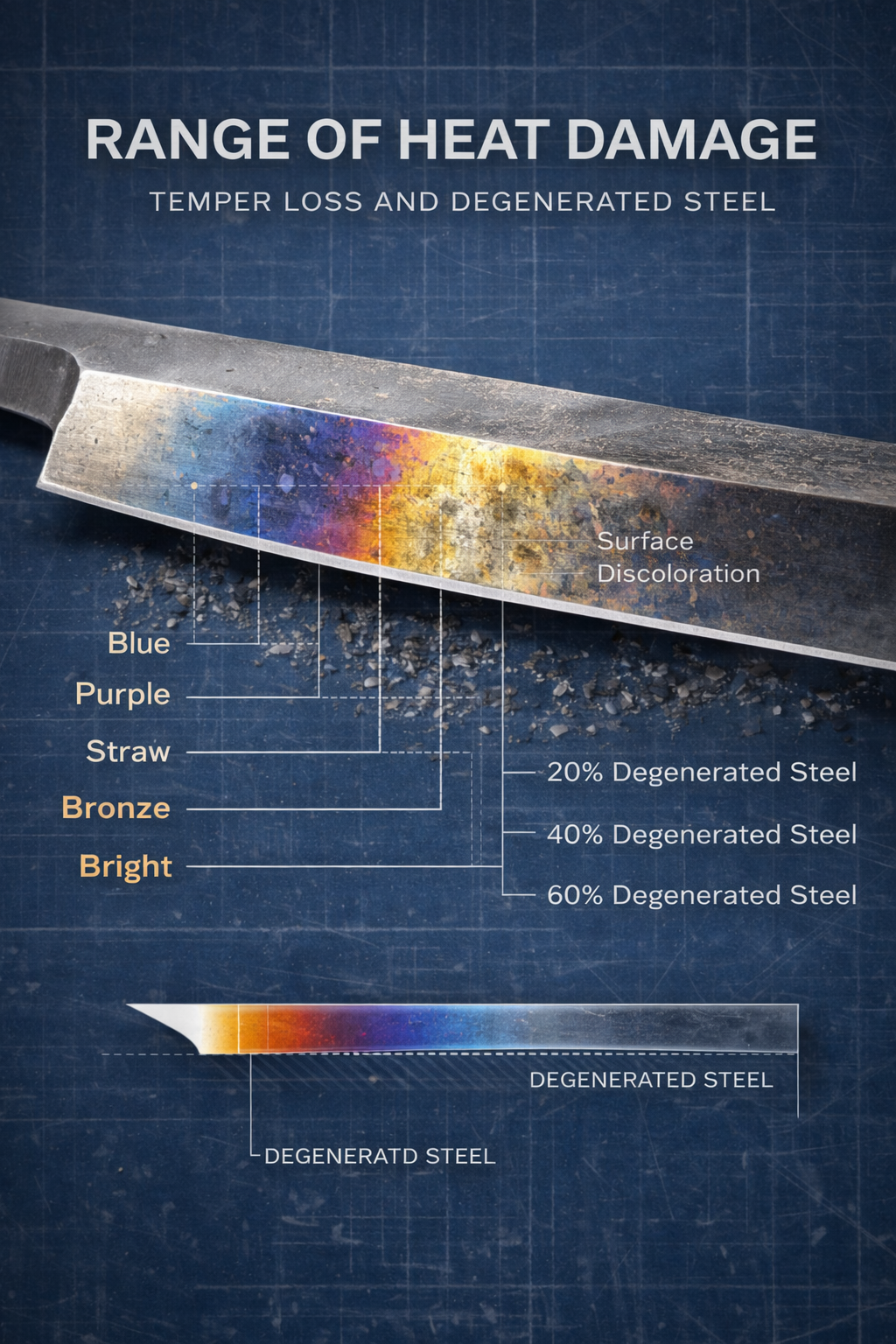

Most people associate heat damage with visible indicators:

Blueing

Straw coloration

Burn marks

Surface distortion

These indicators represent extreme cases.

In professional sharpening, the more dangerous heat damage occurs below the threshold of visibility. Steel can undergo microstructural change long before color or surface texture is affected.

By the time discoloration appears, damage has already progressed beyond correction.

Temper Is a Structural Property, Not a Visual One

Steel hardness and toughness are governed by temper.

Temper is not a coating, a finish, or a surface trait — it is a metallurgical state.

When excessive heat is introduced:

Hardness can be locally reduced

Grain structure can shift

Edge stability degrades

Wear resistance declines

These changes occur internally.

The edge may still feel sharp.

The bevel may still look clean.

The failure only reveals itself under use.

Why “Cool to the Touch” Is Meaningless

A common misconception in sharpening is equating thermal safety with tactile comfort.

Steel can:

Exceed critical temperatures at the edge

Transfer heat rapidly

Cool quickly at the surface

All before the operator perceives warmth.

The thinnest part of the edge heats first and cools first. By the time heat is felt at thicker sections, the damage has already occurred.

Thermal events happen faster than human perception.

Friction, Pressure, and Dwell Time

Heat is not caused by speed alone.

It is generated by the interaction of:

Friction

Pressure

Contact duration

Surface condition

Low-speed systems can overheat steel if pressure and dwell are uncontrolled.

High-speed systems can be thermally stable if contact is regulated correctly.

The variable is not RPM.

The variable is thermal management.

Why Heat Damage Produces False Confidence

One of the most dangerous aspects of heat damage is that it often produces edges that feel exceptionally sharp at first.

This occurs because:

Steel softening allows rapid material removal

Burrs form aggressively

Initial bite increases

This false sharpness masks instability.

The edge dulls quickly, rolls under load, or fractures microscopically — all symptoms attributed incorrectly to use, steel quality, or technique rather than thermal compromise.

Heat Damage Is Cumulative and Irreversible

Once temper is lost, it cannot be restored through sharpening.

Repeated thermal events:

Reduce service life

Increase maintenance frequency

Accelerate geometry loss

Permanently weaken steel

Each sharpening cycle compounds the damage.

This is why tools that were once reliable gradually become “problem tools,” despite appearing well-maintained.

Institutional Standard

Professional sharpening does not assume steel integrity — it protects it.

Thermal control must be:

Designed into the process

Enforced through discipline

Verified through outcomes over time

Any process that relies on visual cues or tactile judgment to detect heat damage is already too late.

Heat damage is not dramatic.

It is silent, cumulative, and decisive.

Preventing it is not optional.

It is foundational to professional responsibility.